Ear Training and Sight Singing

A bit of housekeeping:

In the first post on practice strategies, I made a list of things that a well theorized practice schedule should cover. I’ll be updating that list as I write posts on the subjects.

In the previous post, I talked about using reading and writing, note taking, to your advantage. You’d be surprised at how much writing will help you with things, it’s proving the pudding, if you will. Today we are going to talk about a part of music practice that I find really exciting, ear training and sight singing.

This is, in some sense, the skill that almost everyone associates with music, and it’s expressed as one thing, in two parts,

Ear training

Sight singing

It’s usually described as two things, but I like to think of it as one skill expressed in two dimensions. The name of that skill is music recognition.

Music Recognition

I had this idea when talking to my friend Trevor that a huge part of being a musician is having the ability to discern the music wherever you may find it and in whatever form you may be given it. When I was in music school and taking lessons, they never formally described it in this abstract way, they would consider there to be two things that were distinct

Music appreciation

Ear training and sight singing

Music appreciation consisted of knowing things about significant and influential pieces of music,

about the music, itself

key

structure

defining themes and sections

arrangement

about the context of the music

historical circumstances

trends and reactions

the composer

I have come to see it not as as two separate things, but one thing, in three parts

ear training

sight singing

“music appreciation”

These three things work together to allow us to find music everywhere and to recognise quotations, references and paraphrases. You learn to hear and feel similarities, training your total awareness to be faster than your conscious mind. One of the best examples of this is Canon In D Major.

Rob makes a great joke out of it, but this is what you can do when you have trained your ear to recognise songs, in context and know what they are. It’s not just about the structures, which we’ll discuss a bit later, but hearing the original song in its entirety, understanding what it is, how it’s been used in several other contexts and how it is being used in this context. By discerning such things, we are discovering the dialogic characteristics of music, that is to say, how works of art can be understood as being in conversation with each other.

There are two ways that I, as a teenager, first came across Herbie Hancock’s name, both are samples from hiphop songs.

Us3’s Cantaloop , which samples Herbie’s Cantaloupe Island

Mobb Deep’s Shook Ones, Pt. II, which samples Herbie’s Jessica

Long before I knew anything about Herbie Hancock being in Miles Davis’s band, before I knew anything about Blue Note Records, long before I knew jazz was anything besides my dad’s Louis Armstrong records, I knew that his piano was the one I heard in hiphop songs, and I found out by reading the liner notes to cassettes and CD’s. To this day, whenever I hear a bit of Herbie, especially those songs, I always think of Us3 and Mobb Deep, two very different bands, and I think of everything else I know that samples, quotes or refers to all of these things. All of this forms a chain of associations and meanings, something like the musical equivalent of Indra’s Net.

More than just references and possibilities for interpretation, you can get ideas for improvisation and inclusion, your ability to see how things can fit together is grown.

The best way to learn this is to listen to music, read music and learn music. But, in addition, when you are learning a song, this is a great way to do the equivalent of a literature review. Let’s take the example of Sweet Georgia Brown, which I mentioned is one of the songs that we want to do. Here are some cool versions of it!

There are many, many more. Listen to all the interesting versions you can find, it’s so much easier, now, with music services. In my day, I had to go digging through stacks of records, cassettes and CD’s to find albums that had songs I was looking for. Apple Music can give you hundreds of songs with just a few keystrokes. Listen to the songs, learn the musicians, see who did it, see what else they did, who they played with. There’s a lot there for you to draw inspiration from. Learning to recognise music as songs, in social contexts, adds to the richness and vividness of the joy.

Traditional Ear Training

Traditional ear training is invaluable. Music is, primarily, majorly and ultimately, an art form we experience through sound, by listening and feeling the soundwaves reverberate. Teaching our ears to recognise the sounds we hear as we hear, to discern structure and definition, at every level of abstraction of the piece, note by note, beat by beat, measure by measure, section by section, etc., is critical to understanding what we hear. We need to learn to listen for rhythm, harmony, melody and key. This is a lot!

Playing music is a lot like dancing with someone, you need to be able to give nonverbal cues about what you are doing and what you intend to do to your partner, whether leading or following. You also need to be able to receive them. The cues need to be subtle, so you can keep your attention majorly on the dancing and the shared experience with your partner, and they also need to be only a hint of what you are doing, because you want to preserve the spontaneity and delight. In the same way that you know that you are likely to get a present on your birthday, but now what it is, and the excitement of discovering the present is a big part of the joy of the birthday present, having some idea that you are going to turn to the left is helpful, but you still want some unspecified part of it so that you can add your own elements to it and be surprised by what your partner is doing.

Why do you need to worry about this? We keep talking about your total awareness being faster than your conscious mind, but I’d like you to imagine something even slower, which is having to talk. Imagine two musicians, a piano player and a guitar player, sitting and jamming. If each of them had to call out what they were doing and what they thought the other would do in response to it, they would be talking the whole time. The amount of verbiage necessary to describe a musical idea is significantly greater than the amount of music necessary to express it.

On a more philosophical level, music is the form of art meant to be experienced through the sense of hearing. Training your ear to recognise things as they come to you is not just for purpose of being able to interact with music and push it forward, but to understand what you are hearing as you hear it and appreciate it. A good practice and training schedule will explicitly make time for this.

Traditional Sight Singing

Having just said this about music being experienced through hearing, what is the point of learning to recognise it in writing? You can get into the questions that Plato did in Phaedrus about what writing is and isn’t, but, in practice, writing music is

a good way to lend clarity to what is intended in what we hear

a good way to make music portable

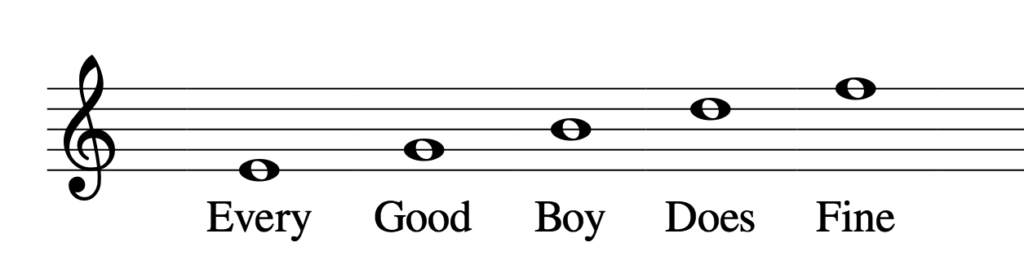

Before getting into either of these, the immediate, practical and functional ability of training yourself to recognise what is written on paper and recreate it with your voice or hands is that you can start playing new music immediately. You can be handed a lead sheet, see the melody and the chords above it and get right to work. If you can immediately associate your hands with scales and chord shapes, it’s a whole lot less work. Again, you are training your total awareness to be faster than your conscious mind, so you can see something and react without having to stop and things like, “Every Good Boy Does Fine, so, that’s a D, which I can play on the fifth fret of the A string,…”

You can simply act without having to direct your action. The visual trigger is enough to activate your knowledge. This, alone, makes the effort invested worth it. You can spend more time refining your interpretation than struggling to implement one.

Now, to hit the two bullet points, the first seems oddly contradictory to what I’d said in the section before on ear training, which is that music is an art form experienced majorly and ultimately through your ears, as auditory. And it is so, in terms of how we take in the art and how we collaborate with others, but, oddly, music is mostly made by players using visual triggers. It takes a tremendous amount of verbiage to describe music, but the formal written language of music is very efficient in communicating enough of music to help you play and understand it.

What do I mean mean by saying that we want to make music portable? By portable, in this case, we mean able to be easily carried and handed to other people. The formal symbology of music makes it very, very easy to tell people

what to play

when to play it

what everyone else is playing

when they will play it

Let’s look at a lesson the magnificent Dirk. Kind of Blue is the greatest selling jazz album of all time. Don’t believe me? Ask the internet. I think that more people think of the opening lick to the opening track, So What, when they think of jazz music than anything else, even Louis Armstrong singing When The Saints Go Marching In.

This song did not involve a guitar, and was put together by a whole band. If we wanted to give the vibe of the song when playing a solo guitar, how would we do it? Dirk’s lesson is a great one, and a great example of a lead sheet. The chart shows the melody and then the harmonic context. We know what’s happening at every beat, so we can understand what we’re playing as we play it.

Not only did Dirk hand off a Miles Davis song to us, but he transformed it by abstracting all the individual parts into the most fundamental representation of it. This chart can be handed to anyone on any instrument, and they’ll know what to do.

Sight singing is the skill that helps us receive the handoff.

So, we’ve talked about complementary skills, training one’s ear and training one’s eyes, so that we can make our systems react faster than our conscious minds. Cool, huh?