Well enough gets awful lonely.

There’s a thing that my mom used to say about someone who causes trouble by unnecessarily digging into things, that he “never leaves well enough alone.” By “someone”, she meant me, her son, but she was polite enough to abstract it to possibly apply to anyone. In my defense, very few things were actually doing well enough. If they were, I wouldn’t need to go digging, and, honestly, I didn’t cause problems, I revealed them.

So, we’ve mentioned learning techniques and songs. But, given how variable a guitar can be, what sorts of tunings are we going to use? To nobody’s surprise, the tradition has many, many masters, who’ve all used many different tunings. Here are the ones I’m going to be using.

There are a few dimensions in which this will vary:

The number of strings on the guitar

How they are tuned

Now, in writing this post, I have come across what seems to be a fatal limit of Substack, which is that you cannot put a table into a post. This, to be clear, is absolutely nuts.

Guitars

I have a lot of guitars. Let’s get that out of the way. Each one is something magical. I love them all. I can tell you what I love about them. We don’t have to have that conversation just yet, though. I’ve compared the feeling of rightness that you have when you have the right guitar to the comfort you feel when you wear a great pair of shoes, something that fits your foot well, that you like the look of and that makes doing whatever you need to do in them, running, walking, dancing, construction, whatever, a breeze. Each of these guitars is like a different pair of shoes, each does something different. How lucky to be able to have each. I have guitars built with six strings and guitars built with seven strings.

The question most of you are probably asking is, “Why seven? Why can’t you leave well enough alone?” The answer is that there’s a lot of very cool jazz music played on seven string guitars, and by some very cool players. Three come to mind immediately,

It’s not just these three, though. They’re just the ones that come to mind. They’ve inspired thousands of players, so much so that you can get get seven string options online with ease. If you are going to buy a seven, do consider buying one from my buddy Matt Raines. He had this idea that buying a seven string should be as easy and as affordable as buying an Epiphone off the rack at Guitar Center, and worked for years to develop one. You can buy a guitar made by a luthier, and it will be awesome, but you’ll have to wait for a long time. Or you can buy a high dollar pre-made one. Or you can buy a mid dollar one for Matt, which is truly amazing.

Tunings

As far as tunings, the reason to retune is to take advantage of a powerful feature of the guitar: controlling which pitches ring open by changing the parameters of the strings. Open strings resonate differently than fretted strings. It’s just a much more vibrant, powerful sound. You can make very cool things happen just by changing which strings are available to you as open strings.

Now, since we cannot use a table, I’m going to have to explain this all a bit oddly.

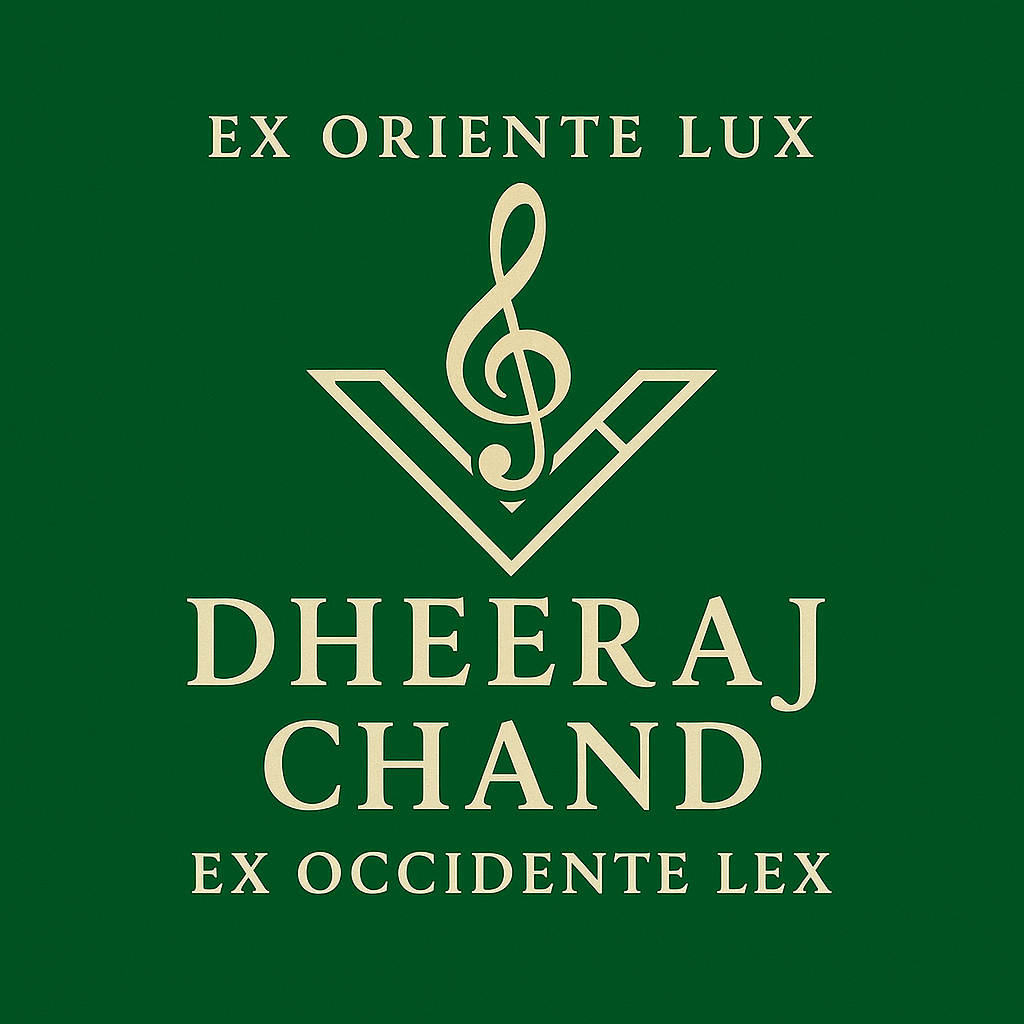

The standard tuning on a guitar is pretty well known:

E

A

D

G

B

E

This tuning is used by the vast majority of jazz guitarists. Almost everything you find will be arranged for this. I will be using a very cool Heritage guitar for this.

There are two ways to go with this, you can do what most people do, which is what I linked above, or you can do the Lenny Breau tuning, which is, strictly speaking, still standard, although an uncommon way to do it. You should consider it. Lenny did amazing things. Leaving aside Lenny’s accomplishments, for now, the common version of the standard tuning on a seven goes

B

E

A

D

G

B

E

What this does is give you a bass string that is in B, making your seventh string identical to your second string. A cool thing about this tuning is that it makes playing scales and modes very easy, you don’t have to worry about offsetting by two frets on the sixth and seventh strings. You also have familiar patterns between the seventh and sixth string, it’s the same patterns as between the second and first string.

The fingerings are pretty straightforward and repeat easily. I’ll be using my Raines 7 for this one.

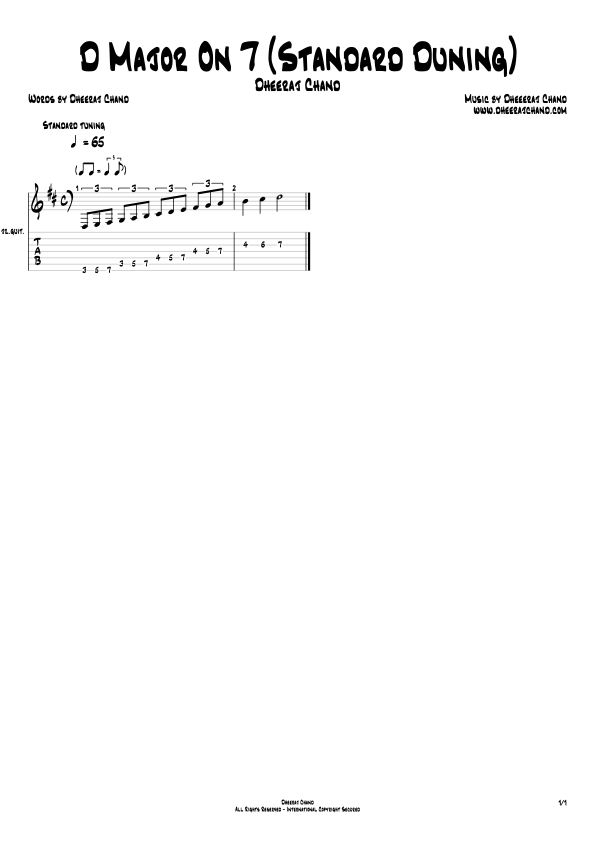

This heading is almost a trick, in that there is no “Van Eps” tuning for a six string. This is colloquially called the Van Eps Tuning after George Van Eps, who used it for quite a bit. The first mass production electric guitar with seven strings was made Gretsch, the Van Eps model. George put his name on that thing for a reason. Those guitars are amazing, which is why I bought it.

There are two significant benefits to this tuning

Your seventh string is even lower, which allows you to get deeper into bass guitar territory

You have an octave between your fifth and seventh strings, which means that you can

imply motion by alternating the note between the fifth and seventh strings, even while preserving the harmony

almost double the number chord voicings available to you simply by moving one finger

This is a very cool tuning, accordingly, but there is a two fret offset between the seventh and sixth strings.

I don’t find this awkward, but it does make playing fast scalar or modal lines a bit trickier. For this tuning, I’ll use my Eastman 7, Gretch 7 and Benedetto 7.

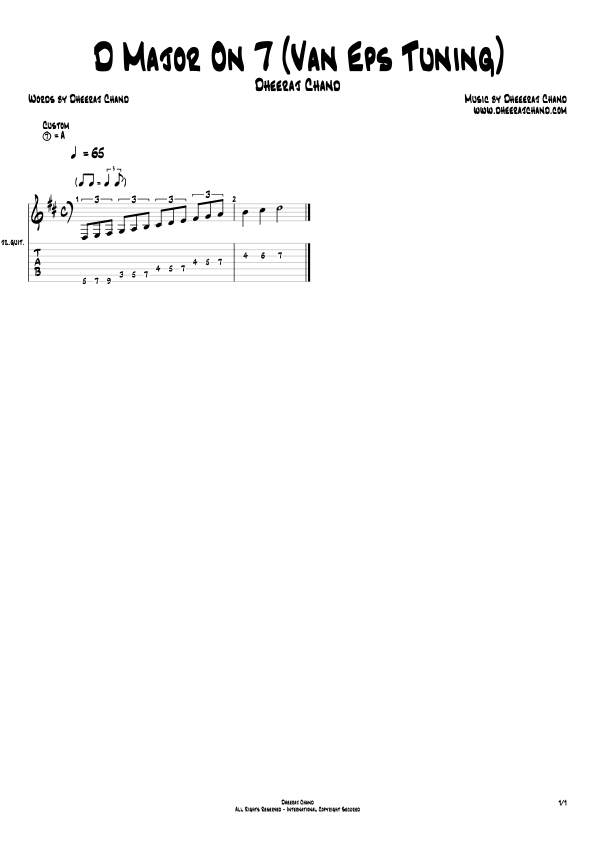

This is one of those tunings that people either love or hate, there are not a lot of people who are ambivalent to it. There are some very cool things about playing in fourths.

You have uniform chord shapes everywhere

You have uniform scale shapes everywhere

You have uniform arpeggio shapes everywhere

Quartal (“four note”) chords become very natural

Standard tuning has one big advantage over this tuning, which is that you have your highest and lowest strings tuned to the same pitch class, E. This means that when you play all six strings, you can have the highest and lowest notes hit the same pitches. But, guess what, most of the time that you’re playing jazz, you’re not playing all six strings, and you’re not likely to play more than four at a time.

A few things to note here.

In order to preserve starting on the third fret of the lowest string, we’ve switched to G Major from D Major.

The pattern on the highest string doesn’t appear anywhere else, which is frustrating.

I’ll be using my Eastman Romeo for this.

Why all this?

Varying it up like this makes it spicy! It makes it even more interesting to see what you can do when you have all the possibilities in front of you. But, realistically, it’s a way of making sure that you can do what you do in more circumstances, some of which may not be familiar or favorable, and it’s a way to make sure that you don’t just remember muscle patterns, that you are learning to cognize even as you do lay down the muscle memory.